Starship SN5 Static Fire Next Week

Plus, meet Bluezilla and discuss how you could pay for your trip to Mars

Welcome friends!

SpaceX and Starship

SpaceX is planning two events for July 8. First, road closure filings indicate a planned static fire test for Starship SN5. This hull successfully passed cryogenic pressure testing with liquid nitrogen on June 30. This video shows one of the Raptor engines being transported, on its way to being installed on SN5:

In addition, the next Falcon 9 launch is scheduled for the same day. This launch will be carrying another 57 Starlink satellites into orbit, bringing the total to 597. It will also carry two RideShare satellites, BlackSky Global 5 and 6, which are commercial imaging satellites. BlackSky is planning to build a constellation of 60 satellites, offering 1 meter resolution and rapid revisit times.

My interest in Starlink here, in the context of humans traveling to Mars and the Moon, is that's how SpaceX plans to pay for ongoing development. Without Starlink, the rest of the program is unlikely to happen.

SpaceX has recently begun construction of a High Bay that will be used to build the Super Heavy (SH) booster. Part of that process is a huge new crane, affectionately dubbed "Bluezilla":

Once it enters production, the first SH launch of a typical manned mission to Mars will carry the Starship that's actually going to Mars, along with passengers and cargo. After achieving Earth orbit, that Starship's fuel tanks will be (almost) empty. Super Heavy's next task will be to land, pick up a different Starship carrying fuel instead of cargo and passengers, then launch again, and deliver that fuel to the first Starship. The fuel-carrying Starship and SH will then both land and repeat the process roughly five times before the first Starship will be ready to leave Earth orbit for Mars.

Getting Ready

If you want to travel to Mars, to either live permanently or as a temporary job or even as a type of adventure vacation, what kinds of things should you learn before you go?

You will of course want to know everything you can about the ship itself: its floorplan, available equipment, food, hygiene, exercise, activities, and so on, as well as all about your spacesuit. This will help you optimize what you pack in your carry-on luggage and the other gear you take with you.

You may also want to spend some time learning skills that will be useful once you arrive. For example, you might choose geology, construction, solar power, Sabatier fuel plant design and operation, cryogenics, water storage and purification, health care, agriculture, and so on. Certain jobs will also be in demand from the Earth side, such as news reporters and documentary film makers. In the early days, it will be important to have more than one skill.

Lining up your financing will be another important pre-trip task. One possibility is a work-related contract, where you agree to perform certain tasks in exchange for your travel costs. You might go to collect rocks to be sold back on Earth, for example. Or maybe work doing customer support or engineering of some kind for SpaceX. You also might be able to raise money by selling assets you own on Earth, such as your house.

In addition to direct payment, I think it's likely that SpaceX will also offer financing of some kind, where you can pay so much per month or per year, like you do when buying a car or a house. One nice thing about being among the first to make the trip is that wages are likely to be higher in the early days than later on, due to the novelty, the relatively small number of travelers, and the perception of increased risk. Things like Mars rocks and perhaps jewelry made from gems on Mars, could be worth a lot on Earth in the early days. Media coverage and interest, too, is likely to be huge.

Getting There

After leaving Earth orbit, Starship's deployment of its solar arrays and communications antenna will be crucial milestones. Without power, the mission will be doomed, and it will be impossible for the ship to turn around.

Adjusting to live in zero-G should be fun, but there can be issues. Some people develop nausea, basically a form of motion sickness. Fortunately, it's treatable. Also, the way objects move in zero-G is very different, since they don't fall. Instead, they move in a straight line until they run into something or someone. This includes water and other fluids, which also means it's easy for them to make a huge mess if you're not careful. You should expect drinks and food that isn't solid to be contained in packages and consumed by squeezing through a straw, as they do today on the International Space Station (ISS). Plates, cups and utensils will have little to no place in zero-G.

Another aspect of zero-G is that you can't stop yourself from coasting without grabbing onto something. If you push away from a wall, there's no way to stop until you either run into something or you’re within reach of something you can grab (like on ISS, there should be plenty of rails to grab with both your hands and feet). Unfortunately, this means it will be easy to hurt others if you aren't careful. Astronauts on the ISS receive training about this. I hope SpaceX decides to require some training for “everyday” Starship passengers, but that hasn't been decided yet.

Living There

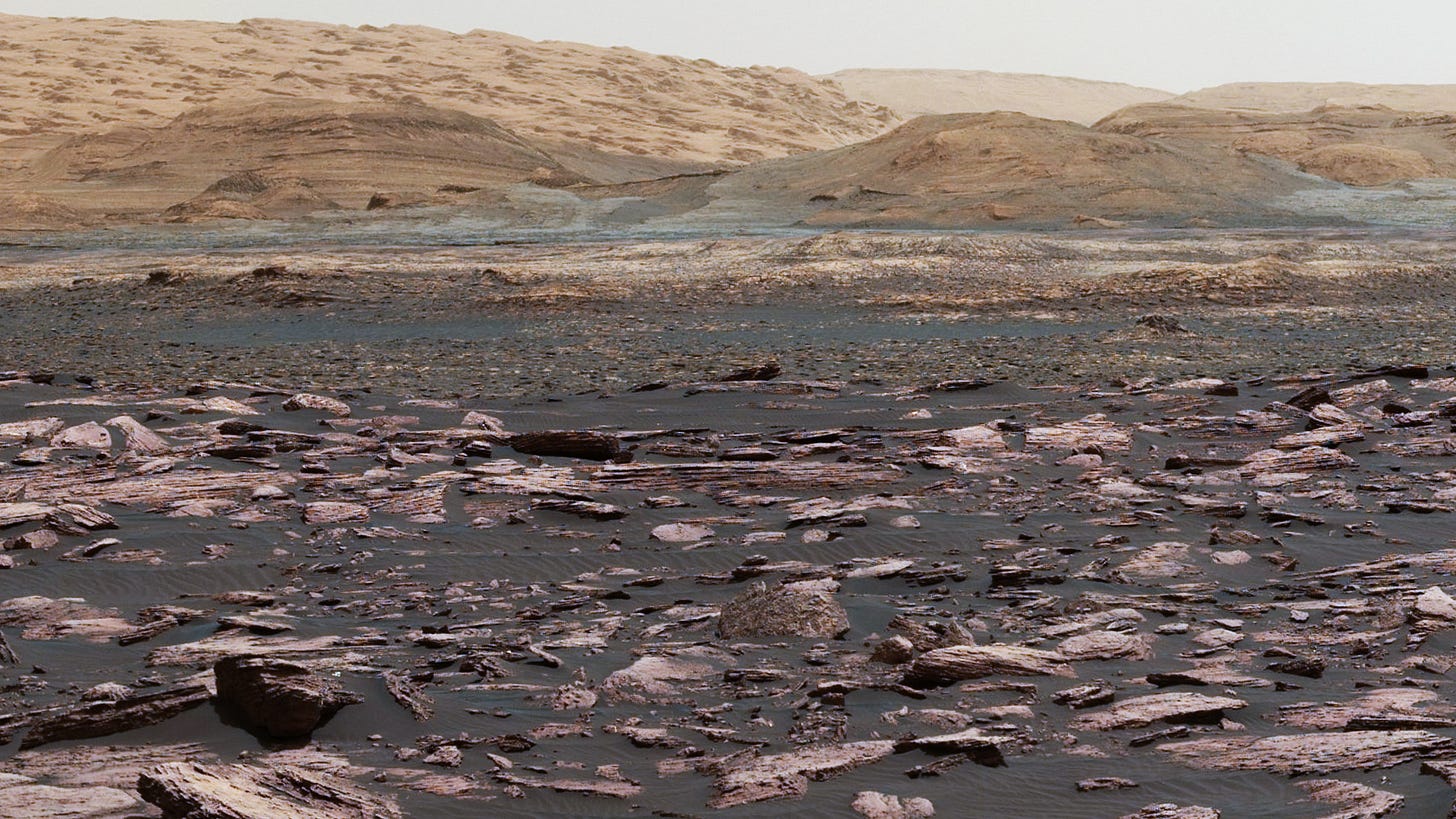

Mars doesn't have a magnetic field; a compass won't work there. Combined with its thin atmosphere, that also means there's much more radiation on the surface of Mars than on Earth. For that reason, I suspect that housing there will ultimately be in structures that are at least a few meters below the surface, rather than in the all-too-common glass domes often shown in science fiction. The mass of regolith on top of underground structures will provide protection from radiation. Digging a few meters down will also be needed to find and harvest water for drinking and for use in producing rocket fuel, so there's good potential synergy.

After arrival, the crew should help unload your gear from Starship, and move it where it needs to be. Early missions may use Starship for shelter, but given SpaceX's strong desire for both rocket re-use and colonization, early development of shelters and housing away from Starship should be a priority.

The first manned missions won't be launched until earlier missions have achieved their goals, which will include finding water and creating the fuel Starship will need to return to Earth. By the time the first people arrive, they should already have at least one fully fueled Starship ready to take them home.

Later on, a typical pattern could be that roughly 30 days after arriving, a ship should be refueled and ready for its departure back to Earth. Most passengers will remain until the next orbital window opens in another two years or so, but if someone got sick or some other emergency came up, an immediate turn-around might be possible. It would still take months to return, but at least it wouldn't be years.

Once you're moved-in and unpacked on Mars, you will have some level of access to Earth's Internet. Due to speed of light delays, though, it will feel klunky. Email should feel pretty much the same; you should be able to send and receive video and audio to your friends and family, but web browsing will be awkward and slow. A similar mechanism should be available on Starship during the trip, so you will have plenty of time to get used to it by the time you arrive.